Sponsored by Lerner Books.

Ash Bishop has always known who he is: a guy who loves soccer, has a crush on his friend Michelle, and is fascinated by his hometown of Salem, Massachusetts. He’s also always known that he’s intersex. It’s never felt like a big deal until Ash gets his first period in front of the boys’ soccer team. Now everyone sees him differently, and his own mother thinks he should “try being a girl” as Ash tries to defend his identity. I. W. Gregorio, author of This is My Brain in Love called this empowering journey “a must read for all humans.”

Hey YA Readers!

In early August, I put together an episode of Hey YA Extra Credit on the topic of the first “true” “YA” book. All of those quotes for reasons that will become apparent. Because this was a scripted podcast, meaning I wrote out and crafted a narrative for it, I thought it would be worth revisiting here. You can listen to the episode in full here, read below, OR take it old school and listen as you read along — I assume other people loved those books on tape that came with the book as kids so you could do both at the same time.

I loved digging into the history here, and I’m hoping to make these semi-deep dives into YA history a regular on Hey YA Extra Credit. Note that this is a longer read, so set aside a bit of time before diving in. Links to sources and further reading are here, and they are super fascinating if this interests you!

Do you know what the first “official” YA book was? The one written specifically for teenage readers, featuring teenage protagonists?

If your answer is The Outsiders by SE Hinton, you’re close, but you’d be wrong. It’s a different title, published decades prior, and one that is still in print today.

The First YA Book

The year is 1942. In America, teenagers aren’t yet considered a whole separate demographic. Sure, they’re young people, but the idea of their power as a group of consumers hadn’t yet been tapped. That would come after the war.

|

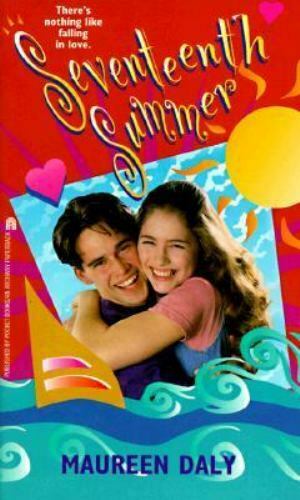

While many writers featured adolescents in their books at the time, as well as prior to, crating work specifically for teen readers had yet to come into vogue. Paul Zindel and SE Hinton would come to define early YA books in the 60s, but it was Maureen Daly’s Seventeenth Summer which most commonly earns distinction as the first book for and about teenagers.

Maureen Daly was born in Ireland, moving to the US in the 1920s. They settled in the mid-size town of Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin, and Maureen attended St. Mary’s Springs. It was one of her teachers, Sister Rosita Handibode, who encouraged her to write and helped her lead a fascinating career, starting at a remarkably young age.

Seventeenth Summer is the story of Angie Marrow, a 17-year-old who just graduated from a private, all-girls prep school in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. That summer, she catches a glimpse of Jack Duluth, who graduated from the local public school. It’s ultimately a story about middle class teenagers falling in love during a summer when all things are setting up to change — Angie is preparing to go to college in the fall, whereas Jack is planning to go work the family business.

While the book is ultimately a love story between two teens on the brink of adulthood, it’s also a keen story of life for middle class white teens in the pre-war era; Jack’s family owns a successful bakery, while Angie’s mom is a strict parent, often left to parent alone while her husband, Angie’s father, travels for his job in sales.

Here’s a short excerpt, exemplifying the class differences and sensibilities. Note that throughout the book to this point, Angie’s been defending Jack’s status, but it’s clear here, there’s a difference in their upbringing and she’s starting to see it.

“In our house where we had never been allowed to eat untidily, even when we sat in highchairs! It all seemed so suddenly and sickeningly clear – I could just see his father in shirtsleeves, piling food onto his knife and never using napkins except where there was company. And probably they brought the coffee pot right in and set it on the table.

My whole mind was filled with a growing disdain and loathing. His family probably didn’t even own a butter knife! No girl has to stand for that. Never. If a boy gets red in the face, sputters salad dressing on the tablecloth, and hasn’t even read a single book to talk about when you ask him over for dinner, you don’t have to be nice to him – even if he has kissed you and said things to you that no one has ever said before!”

|

Jack and Angie have their first date together at a bar — not unusual in Wisconsin — and the book is peppered with them drinking and smoking. Lorraine, who is Angie’s sister, stars in a thread through the book about the challenges of coming back home for the summer after being away in college, offering a peek at what Angie and Jack might be in for should their relationship last.

This isn’t a romance with a happily ever after. In the end, we see Angie choosing one path, while Jack is forced into a different one. And though the emotional notes and dated references and language situate the book in its time, there is a sense of timelessness to the story, too: what happens when you fall in love during your teens? What happens when that love is doomed from the start? And what happens when family meddles into those affairs: do you pursue romance or do you consider what it is your family is saying?

The History of Seventeenth Summer

|

Seventeenth Summer has, believe it or not, been in print since its first publication. In some of the publicity for the book, it’s called a refreshing alternate to “modern” love stories — which is interesting to unpack, especially if “modern” in that publicity refers to, say, sex positive titles or titles featuring characters of color, queer characters, or anyone living at the intersections of various underrepresented groups.

Many contemporary reviewers of the book note that it’s long and very little happens — there is little kissing or hand holding and far more looking off into the distance together. Many note that Jack and Angie never even really talk to one another, despite how much there is for them to discuss.

Other modern critics disagree with both. Some find the book to be subtle in its portrayals of love and romance, with a softly simmering sexuality that becomes more apparent the closer one reads.

Over the course of eight decades, Daly’s book has remained in print, rereleased with a new wave of publicity in 2010. An audiobook, performed by the award-winning Julia Whelan, came out the following year, introducing a whole new audience to the classic. It has sold more than a million copies. Though initially released as an adult book — remember the category of teen or young adult hadn’t been developed yet — it was, without question, for that audience and in subsequent decades, found its way through those publication channels.

Seventeenth Summer was reviewed in the New York Times, noting the success of the novel and attributing it in part to Daly’s closeness to the characters: “By a kind of miracle, and perhaps because she is so close to an experience not easy to recapture, Miss Daly has made an utterly enchanting book out of this very fragile little story — one which rings true and sweet and fresh and sound.” Many reviewers at the time praised the book, even though it was held to adult novel standards, due to there being no actual young adult category to which it could be compared.

Of the book, Daly said “It was a sheer outburst of creative yearning and emotional hype. I loved that town (and several of the young men in it) and wanted to express myself and my feelings at that time.”

|

Seventeenth Summer was Daly’s first novel, but it wasn’t her first brush with publishing or writing. When she was 15, her short story titled “Fifteen” was published by Scholastic magazine — it earned a third place distinction in their annual contest, and at 16, her short story “Sixteen” earned a first place finish in that contest and was included in O. Henry’s best short stories. She wrote Seventeenth Summer in her parents’ basement after, but it wouldn’t be until she went to college the book would see publication. It was, once again, in part to a contest — this time, in addition to prize money of $1000, her book would be published by Dodd Mead.

After Seventeenth Summer

Despite her success, Daly didn’t continue publishing books until much later. She pursued a career in newspapers and magazines and while working at the Chicago Tribune, she developed and wrote a popular advice column for teenagers called “On The Solid Side.” It was so popular, it ran three times a week and became syndicated across the country to over 34 papers; her sister took up the column in later years. She wrote under the name “Chi Chi” Daly, answering questions like how to avoid necking and whether or not to drink on a date. A TIME Magazine article quoted her salary for her career during this time at $22,000 — roughly $250,000 today.

Daly also reviewed books and many of those reviews are searchable on newspaper databases. When her husband died, though — he himself a mystery writer — she picked up writing books again and published more titles for teens and for adults.

A fun anecdote worth sharing here — Daly met her husband in what could only be described as a storybook scene: he bought a copy of Seventeenth Summer at Marshall Fields, where she was signing, and had to return to the store for another copy after he lost the original in a cab.

Daly died in 2006 at the age of 85. Film rights to the book were sold, though no film was made. Her 1964 book The Ginger Horse was made into a film.

Her work opened the door to similarly themed books during the era, including books Practically Seventeen by Rosamond du Jardin in 1949, Lenora Mattingly Weber’s Beany Malone, and Fifteen by Beverly Cleary, published in 1956,

It’s incredible to think about the history of this book and how it not only spurred an entire category of books, but it really brought to focus the importance of adolescence as a distinct time period in a person’s life. The book’s pre-war setting, too, is tremendous in what it offers for this demographic of teenagers, unaware that everything they once thought they knew would be completely upended and more, that their demographic would take on significant power socially and culturally just a decade later.

|

You can also trace the history of the book and the history of the marketing of books for teens — and specifically teen girls — through the cover evolution of Seventeenth Summer as well. The 2010 edition mirrors the cover aesthetics of that era, with two pairs of bodyless and faceless legs dangling off a dock into a lake, while the 1985 hardcover edition has a very teen television show feel to it. The 70s edition is reminiscent of Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss, Jack and Angie in 70s-styled clothes.

The original cover? Very much of the “trying to look like an adult novel without trying to look like an adult novel” variety.

Should you pick up Seventeenth Summer if you haven’t? Maybe, maybe not. I personally haven’t, primarily because I think the story behind the story is likely more appealing to me than the book. But readers who want to read a slice of history, who want to see where and how YA came to be, as well as how the category has remained true to its roots, even with tremendous growth and far more inclusivity, perhaps it’s time. How many of the YA books we love follow the contours of first falling in love, navigating challenging familial relationships, and understanding one’s class status? More, how many utilize that first post-high school, pre-college setting to represent standing on that tentative precipice of adulthood?

And luckily, it remains in print and in audiobook format, making accessing Angie and Jack’s summer-before-college love story possible.

Thanks for hanging out, and we’ll see you again on Thursday!

— Kelly Jensen, @heykellyjensen