Good end-of-August, YA lovers!

This week’s “What’s Up in YA?” newsletter is sponsored by Harmony from Europe Comics.

This week’s “What’s Up in YA?” newsletter is sponsored by Harmony from Europe Comics.

One day, Harmony wakes up in an unfamiliar basement having completely lost her memory. All she now knows of the world is the name of her “host,” the mysterious voices in her head and a newly discovered talent for telekinesis. She’s going to have to get her memory back pretty quickly in order to face the dangers that await her. There are so many unanswered questions, and the fight has only just begun…

I know what you’re thinking: she’s going to write about that terrible YA article this week! And you’re right. I am.

But not in the way that you’re expecting.

Instead, let’s talk about what makes literature important, what makes literature leave and impact, and what it is, as a whole, that makes some books “more important” than others.

I’ve pondered before what a YA canon might look like. What are the books which are so important in the YA world that we’ll be reading them forever? That we’ll consider them foundational books in the YA world? What are the books which the teenagers of the next generations will not only read, but will also potentially study in their high school or college classrooms and dissect, seeking out the meaning behind an author’s choice of giving their characters red shoes and green eyes?

Let’s take this a little bit further. We know what books are considered essential, important, and “literary” works — they’re the classics, the bulk of which are written by white guys in history who had the time, the money, the luxury, and the status to write and be published well. Not all of the books we know as part of the canon now were seen that way during their publication, just as there are plenty of books that were wildly popular throughout history that have been forgotten completely.

But those books, regardless of their status as classics in the canon, still left a tremendous impact on culture during the time, as well as long after.

Have you ever heard of the book Trilby by George du Maurier? Published in 1894 in Harper’s Monthly, it was a wildly popular story that sold hundreds of thousands of copies in the US. I wouldn’t be surprised if your initial reaction is never having heard of it. Regardless of being a runaway bestseller in the US and abroad at the turn of the century, it’s a book that is difficult to track down now, as well as a book that’s not read or considered part of the literary canon. It’s not one you’ll likely find in your public library (though it is available in some).

I’ve referenced that book before, and I reference it here again because the power of the book hasn’t left our culture, despite the book itself not being part of the classics/canon. You’ve heard of Svengali, right? If you grew up in a certain era in the Midwest, especially in the Chicago area, you might be familiar with the hosted horror show Svengoolie.

The lineage of both Svengali and Svengoolie can be traced back to Trilby. (There is, of course, a lot to be said here about the antisemitism of this character, but for the purposes of this newsletter, know that that’s a thing).

It doesn’t end there, though. Surely, you’ve heard of the trilby hat? That, too, can be traced back to Du Maurier’s novel, and it was one of the popular fashion trends for men in the UK; it’s still in production and seen throughout the world even today.

Oh, and Trilby has been credited as a major inspiration for The Phantom of the Opera.

If a book has this much cultural power, even more than a century after its publication, how come it isn’t something we’re studying more closely in literary circles or in our literature courses?

Because sometimes, the power of a book isn’t in its longevity or in its power to be part of the elite “literary canon.”

Sometimes the power is in the cultural impact a book has when it’s published, as well as long afterward.

Where Nutt uses his platform to talk about how today’s teens — especially boys — are being harmed by popular YA literature, what he’s getting at is that he is worried about his place in the literary world as a white guy. While YA isn’t great at being inclusive, the calls for it to become more aware of these faults and fix them is a huge aspect of the YA world right now. YA is where female writers, as well as female characters, have had the chance to have a space, to be heard, to have power, to explore the limits of their worlds.

These are the things that, Nutt argues, are harmful.

And they are harmful precisely because they are not part of the White Male Literary Canon.

YA is a young category of fiction, and it’s one that’s ripe for being picked at, for having think pieces written about, and for being called harmful, shameful, and awful for teen readers. Of course, those arguments come from adult readers, many of whom still reference 10+ year old titles in their quest to sound relevant.

Whether or not YA remains robust and begins to build its own canon of literary masterpieces, what matters today, right now, and what will matter for decades upon decades, is that YA has a social and cultural currency that cannot be argued. How much of our language, how many of our references, and how many of our cultural connections come from YA? How much of our shared understanding of the world around us will emerge from our engagement with books like those found in YA?

Patronus.

Katniss.

Mockingjay.

Sparkly vampires.

The Feels.

Even if you don’t know where those references come from, chances are you know what they are or you’ve heard them in regular conversations or used them yourself. Phrases like “patronus” from Harry Potter become woven effortlessly into our vocabularies, used in place of highly appropriative phrases that might otherwise be used. You find yourself with a case of “the feels” after a great read or a great movie.

These are things that connect us with one another. These cultural references, pulled from the YA world and YA literature, have as much pull and importance as the books that we consider classics. The importance might not look the same or feel the same, it may not be studied in the same way in classrooms, but it still matters.

Perhaps there is a reason these titles are so frequently referenced in pieces that argue YA’s value/harm/etc.

Rather than decry another article about how YA is ruining readers, why not instead spend some time reading the incredible journalism, the thoughtful and heart wrenching, the blood-splattered and pain-driven, the joyous and the insightful pieces that pepper the entirety of the YA world, both in the literature, as well as in the blogs, the websites, and from the people who are passionate and driven by this category of books?

I know which matters more in the long run.

100 years from now, even if we don’t see The Hunger Games or Twilight or The Fault in Our Stars or any number of other wildly popular, bestselling YA books in the limited canon (either in the YA world or broader literary world), their impact does not change. The #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement, the call for more inclusivity, the calling out of problems in the YA world, the pointing to these huge books as being extremely white (and the responses to seeing these books not represented that way on the big screen), those things matter and come directly as a result of being able to share in the common interests and passions for literature and good, representative reading.

Instead, it carves a path toward more and more connection, more and more commonality, between us and the world around us.

And that matters, too.

____________________

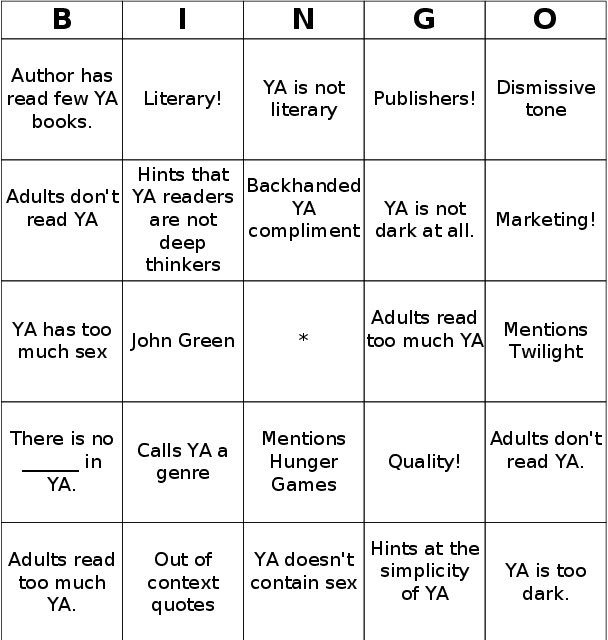

A big, fat round-up of YA news will come your way in the next edition of this newsletter. In the mean time, if you’re still feeling a little worked up over that article, why not pull out YA author and Book Riot contributor Justina Ireland‘s handy little YA article Bingo card and go to town?